# Preface

In June 2020 we started bootstrapping DXP Cloud. The team size was no greater than 2 engineers, and we went out to lay the first bricks of what was to become DXP Cloud.

Quickly we realized that using Azure’s portal as the primary interface for building our platform would not scale, throughout our journey, we iterated over how we’d use IaC and how we could improve. None of us had prior experience in using IaC, but as software engineers, IaC came as a natural adaptation and extension to our DevOps mindset.

# The High Level Design

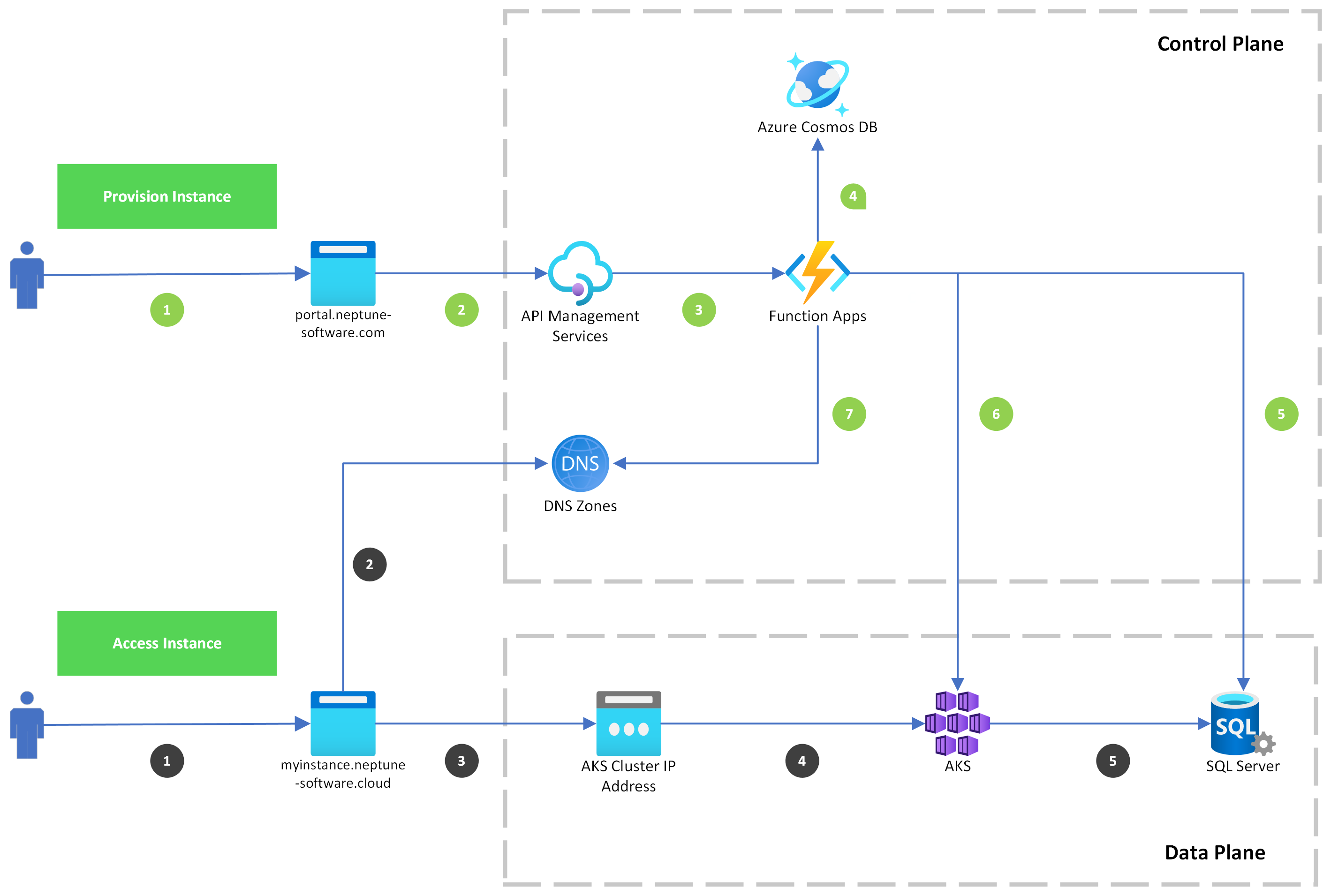

I've decicated a short blog post on explaining what DXP Cloud is and how it works. However, I'll steal the diagram for a moment to discuss a few things.

In our architecture we have static and dynamic cloud resources. Most cloud resources in our Control Plane are static, meaning, they don't create, delete, change on their own. Cloud resources are created, changed, or modified as an actual change to our architecture. Dynamic cloud resources are created, deleted, modified, continiously without being a change to our architecture. Majority of our Data Plane cloud resources are dynamic, which are resources related to our customer's distinct instances.

We can define the Static Infrastructe mostly as the "platform itself", while the Dynamic Infrastructure are the resources that run on top of our platform.

Static Cloud Resource Example

Our Azure API Management Service. This is only modified, when one of our engineers would like to expose a new REST API endpoint.

Dynamic Cloud Resource Example

An Azure SQL Database, provisioned for a new customer instance. This database is solely provisioned for given instance, and can be deleted or modified by the customers initiative. The creation of this resource does not change the actual architecture of DXP Cloud.

# Why differentiate between Static and Dynamic?

This is important, as we'll need to take different approaches on provisioning and managing the cloud resources. This means our IaC journey has 2 parallel storylines. Therefore, the Static Story and the Dynamic Story.

# The Static Story

# Ground Zero

At first, we started fooling around with Azure's Portal. Which provides a great “exploration” experience, but results in manual work. We as engineers hate manual work, we want to automate everything! As manual work doesn’t scale, you can’t version it, you have to document it (ugh) and we’d have to duplicate all of it (Dev and Prod environments)!

Let’s move on and iterate over these shenanigans!

# Iteration 1: ARM Templates & Powershell

One of our principles is “Start off with native tooling when available, and pick another once the existing tooling becomes limited and you understand the requirements”, as we were only with 2 engineers, we can’t afford to educate ourselves about tens of 3rd party tooling, and be productive!

We started off with a single GitHub repository for versioning and collaboration. ARM Templates gave us a declarative approach to define our infrastructure. However, we still end up relying heavily on Powershell cmdlets and the Azure CLI because of operations that were not supported with ARM templates, or are not related to ARM itself (e.g. generating certificates).

The use of Powershell and Azure CLI introduced an imperative approach in combination with a declarative approach from the ARM templates. The combination of those made it very difficult to understand what the “expected” outcome would be from running any of our scripts and any dependencies between resources (e.g. which resource should be provisioned first).

Powershell proved itself to be not very platform-independent friendly (between Windows, macOS, and Linux). Powershell core was supposed to be a solution for this, yet we faced many challenges with running our scripts on any machine. The use of these imperative scripting languages made it harder to run our scripts in an idempotent fashion, which is a top requirement if you want to keep multiple environments in sync.

Adopting git, scripting, and ARM templates, we felt already much more at home as software engineers, yet the complexity grew too quickly with every resource added to our platform. It was time to improve our methodology.

# Iteration 2: Terraform by beginners

The mix of declarative and imperative didn’t sit with us well. After some research, we decided on adapting Terraform as it would remove our need of combining “imperative” and “declarative” methodologies and use solely a declarative approach.

The main concern was that, as Terraform is a 3rd party tool, it would not keep pace with the latest and greatest compared to Azure’s own tooling. However, in return, we would get a much cleaner, declarative approach to defining our infrastructure, in a less verbose file format (HCL, Hashicorp Configuration Language). It would require some education, but the returns on investment seemed worthy.

We spent some days reading “Terraform: Up & Running by Yevgeniy Brikman” which really helped us kickstart the rollout of Terraform. At this point, we were very satisfied with opting for Terraform as our primary tool for IaC. The migration took about a month if memory serves me well, but thanks to the import feature, we didn’t have to start from scratch.

However, no solution is perfect. Did face some other issues now:

- Setting up the “central state file” management that comes with Terraform.

- Setting up a “Plan, Approve, and Apply” pipeline for deployments.

- After importing everything into Terraform, we had a monolith antipattern as we had all of our resources in a single module. This makes Terraform slow, and violates any principles of testability, decoupling, and reusability

# A painful error

Any learning journey isn’t properly told without mentioning some of its failures. This is no exception, at this stage we were adapting Terraform and working on concurrent branches. After some miscommunication and human mistakes (as per usual) we wiped out our AKS cluster with running instances on top of it. The good thing, it was only internal customers (employees) at that point that were using it, the bad thing, it was a painful reminder of the lack of disaster recovery. Restoring was a painful, slow, manual process. Thankfully, only a handful of employees used it at this point.

What went wrong? If memory serves me well, we were working with 2 of us on different branches. One on the master branch and the other on a separate branch. This separate branch had for some reason (been too long to recall the exact reason) not the AKS terraform resource specified, while in the master branch it was. It was already general knowledge that we were not allowed to do “Terraform Apply” from any other branch than the master branch. Yet, by human error, not verifying the current branch, and then not carefully inspecting the plan, we went ahead and applied, dropping our AKS cluster.

We actually understood the problem risk, the risk, and what not to do, before this error happened. We knew what not to do, yet, we still made those exact mistakes, in the exact order that would cause such an issue to happen. The key takeaway is, build your workflow to protect from human mistakes, don’t trust yourself to always have a sharp mind. Do however, try to avoid decreasing developer productivity.

As I am trying to recall this story to write it down, I'm painfully reminded how important Postmortem's are. However, did adopt that practice at a later point

# Iteration 3: Terraform by adolescents

Around this time, Terraform Cloud was launched and offered us an answer to two of our last paint points. “Plan, Approve and Apply” pipeline for deployments and centralized state file management. In addition to that, we’d learn that it solved an unknown challenge for us at the time, providing a private Terraform module registry.

Now, this methodology has started to satisfy our DevOps needs! But we were still facing a new big challenge, we had a single, monolithic Terraform module for our entire infrastructure. At this point, we started to look at the bigger dependencies and scopes that we had in our infrastructure. We sliced our monolithic module with the mindset of “what infrastructure moves, evolves, and deploys at the same pace”.

The end result was that our Terraform “Plan” actions got shorter, as the modules were smaller and could move independently. This was a great first start, however, our modules were still not small, decoupled, reusable, and testable. A single module would still have a strong coupling with other modules, therefore we could not install a module independently, because it required to have many other resources to be provisioned that were not within the module itself. A strong code smell!

Thanks to the Terraform module registry, offered by Terraform cloud, we could easily create and host private Terraform modules as we were breaking down our infrastructure into smaller modules.

# Iteration 4: DevSecOps and Testing

At this point in time, we were quite happy, we have a good deployment pipeline, we have smaller modules, we’re gradually decoupling. Our entire workflow really starts to feel like a software development pipeline! Still, some work is to be done on decoupling our Terraform modules, but a change in architecture and modules is a constant, so we can’t ever claim to be “done”.

What were we still missing from our workflow then? Security and testing!

Security: We wanted to make security a more integral part of our pipeline, often referred to in the industry as “shift left”. We adopted Checkov in our pipeline (https://www.checkov.io/).

Testing: As we had discovered that our modules were strongly coupled to other modules, unit testing our Terraform modules was not an option at this point, refactoring our modules into smaller, independent modules would take a longer time. So we focused on the top of the testing pyramid (opens new window) and created e2e tests, which are run via GitHub actions. These tests are api calls to our DXP Cloud REST API, which then validates if the resources are properly manipulated.

# Iteration 5: Best Practices and Compliance

As our experience with Terraform and IaC had been growing, we started to come up with "tech visions". Documents that define our "best practices". This can be about on how to setup an Azure Function with CI/CD in our environment, or on how to create a new Terraform Module, with the right GitHub actions, branches, etc...

These best practices create a more uniform approach accross our DXP Cloud landscape. To track how we're doing on some of this best practices we use Azure policies to check the compliance. This provides us with some metrics on where we stand. However, a 100% compliance is not our goal as we talk "Best Practices", like "Golden Paths" (opens new window), which should not be mandatory!

Here we start to experience more maturity on how process and methodology.

# Iteration X: The future

There is no final stage of completion, our journey continues and will never end as we keep improving how we work, think, and apply IaC. We can however, share a shortlist of ideas what we’re focusing on:

Refactor Modules: Further redesign, refactor modules which are more testable, reusable, and encapsulated. Quality Assurance: Stronger linting, and static analysis of our modules for better security by adapting tools like tfsec (tfsec.dev). Security: A must have more research on how we can have better security and policies in place. (e.g. Auto scanning all resources on Azure, etc …)

# The Dynamic Story

# Iteration 1: Helm's Deep

In our initial approach, we used Helm for provisioning our Kubernetes resources in a declarative fashion. Helm is a sort of package manager and templating tool for kubernetes. For all Azure resources we use REST API’s , using Azure’s official NPM Packages that wrap those API’s where possible.

The orchestration of provisioning and modifying dynamic infrastructure happens through Azure Functions written in JavaScript. These functions would then use Azure’s NPM Modules that wrap the REST API’s conveniently for the provisioning of Azure Resources. For Kubernetes resources, we’d use Helm. Helm is a templating tool which helps to provision and manage Kubernetes resources.

# Iteration 2: Helm's Too Deep

As we added more support for modifying resources on the DXP Cloud platform, we felt it was more convenient to use the official Kubernetes NPM Module instead of Helm to manage and modify resources. To make our methodology and workflow more consistent, we decided to remove the use of Helm all together for our dynamic infrastructure.

All of our dynamic infrastructure is now operated on via Azure Functions and the official NPM packages of Azure and Kubernetes, which eventually just wrap their respective REST APIs.

We’ve also looked into some tools like Pulumi, but at the time of writing, we had no argument or case to move away from using the native API’s of Azure and Kubernetes for our dynamic infrastructure.

# Iteration X: The future

All our logic is now entirely imperative. Which is still very challenging in debugging and making changes to our data plane. Let's say we want to set tags on an Azure SQL Database when we provision it. That's the easy part, find in our source code the "provision database" logic and modify the code. But what about all of these existing databases? They don't have those tags? We need to build now a specific, one time migration script to update all existing databases. That's usually a bigger task than the actual feature change!

Such use cases come forward all of the time. Therefore, we need to find a better approach on how to manage our dynamic cloud resources. What we need is some "declarative" model (just like Terraform's HCL). So we can define a declaritive model for a given instance. With this, we can rerun the same logic, for all instances, which results in regenerating the declaritive model for each instance.

Once we have regenerated these declarative models for all instances, we can just run a job that reconciles (opens new window) the declarative models with the real world. Exactly as Kubernetes, Terraform (opens new window), and other declaritive IaC tools. However, we must be able to use this in an automated fashion. Terraform, given it's nature of it's state file, would not be a good match. Kuberenetes tooling is too limited, our instance resources cover Azure and Kubernetes resources.

There are some potential candidates out there, aside of homebrewing some solution. However, that is a project and post on its own.

# Resources

Throughout our journey, we use the following books as inspiration for defining and improving our IaC methodology:

- Infrastructure As Code (by Kief Morris, 1st & 2nd edition)

- Terraform: Up & Running (by Yevgeniy Brikman)

- Database Reliability Engineering (By Laine Campbell & Charity Majors)

- Site Reliability Engineering (By Betsy Beyer, Chris Jones, Jennifer Petoff, Nial Richard Murphy)

- Building Evolutionary Architectures (By Neal Ford, Rebecca Parsons, Patrick Kua)

- Fundamentals Of Software Architecture (By Mark Richards & Neal Ford)

# Thanks

I mentioned that we were 2 engineers, but what I meant was that we were with 2 engineers at any given time. I’d like to give a shout out to Kolbjørn and John Inge from Skyetec and to Sebastian Augado who is now a full time member of the DXP Cloud team.